This year, 2021, is the bicentenary of Napoleon's death. Among the scores of books published to coincide with the anniversary, Ruth Scurr's Napoleon: A Life in Gardens and Shadows stands out. Scurr charts Napoleon's extraordinary career not through military campaigns but rather through the gardens that Napoleon planned, financed and personally tended during his life. The Napoleon that emerges is less a military strategist than a would-be savant; the patron of botanists, designers and horticulturists, who finds pleasure and solace in ordering the natural world. Remarkably, it is possible to pursue this story even further, to trace a natural history of Napoleon's afterlife.

Following his defeat at Waterloo in 1815, Napoleon was confined for six years on St. Helena, a south-Atlantic island stronghold administered by the East India company. Located at the intersection of trading routes, the island was a re-provisioning stop for vessels on the return voyage from India. St Helena's varied climates and location, connected ‘with the four quarters of the world’, made it ‘admirably adapted for being the resting place of such plants as are journeying from one of these regions to the other; where the sickly may regain in a congenial climate their natural vigour’ (Flora Sta. Helenica, 1825: i). The island's botanic garden functioned as a key staging post in the network of colonial botanic gardens: receiving and exchanging plants between Britain, the West Indies, India and the Cape of Good Hope (McAleer, 2016). With an additional 2,000 troops and personnel stationed on St. Helena, the island was considered sufficiently remote and well-guarded to contain even a Napoleon.

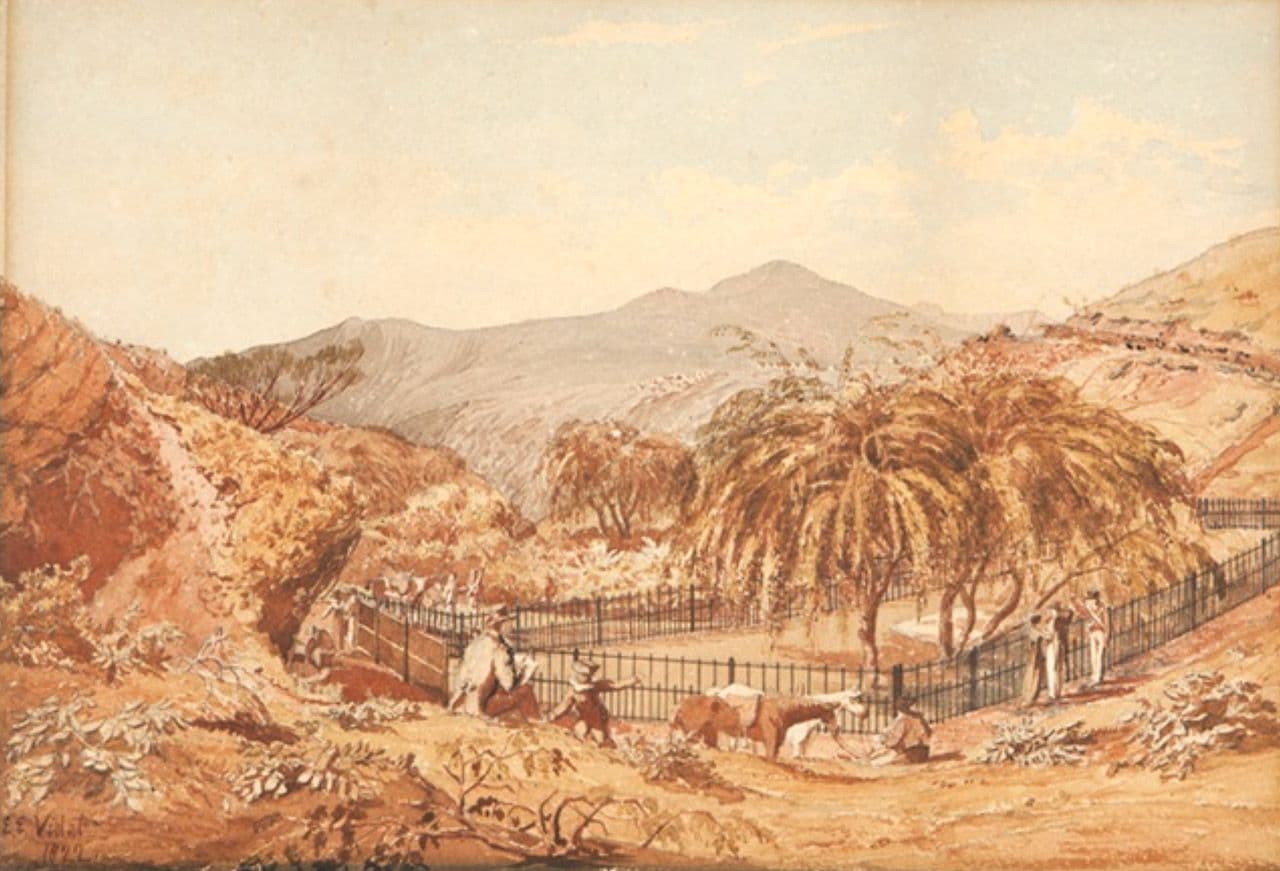

Over the years of exile, Napoleon's health and vigour declined markedly. In his will, Napoleon requested that he be laid to rest on the banks of the Seine; but failing this, he indicated a spot in a neighbouring valley on St. Helena, near a spring which supplied his drinking water. This was a favourite destination for Napoleon's walks: a green retreat, with roses and geraniums, and a seat for contemplation, shaded by a weeping willow. Salix babylonica, like much of St. Helena's flora, was not native to the island. The weeping willow was introduced to St. Helena around 1810; one of the few trees to survive the depredations of the island's goats (Loudon, 1844: 1511).

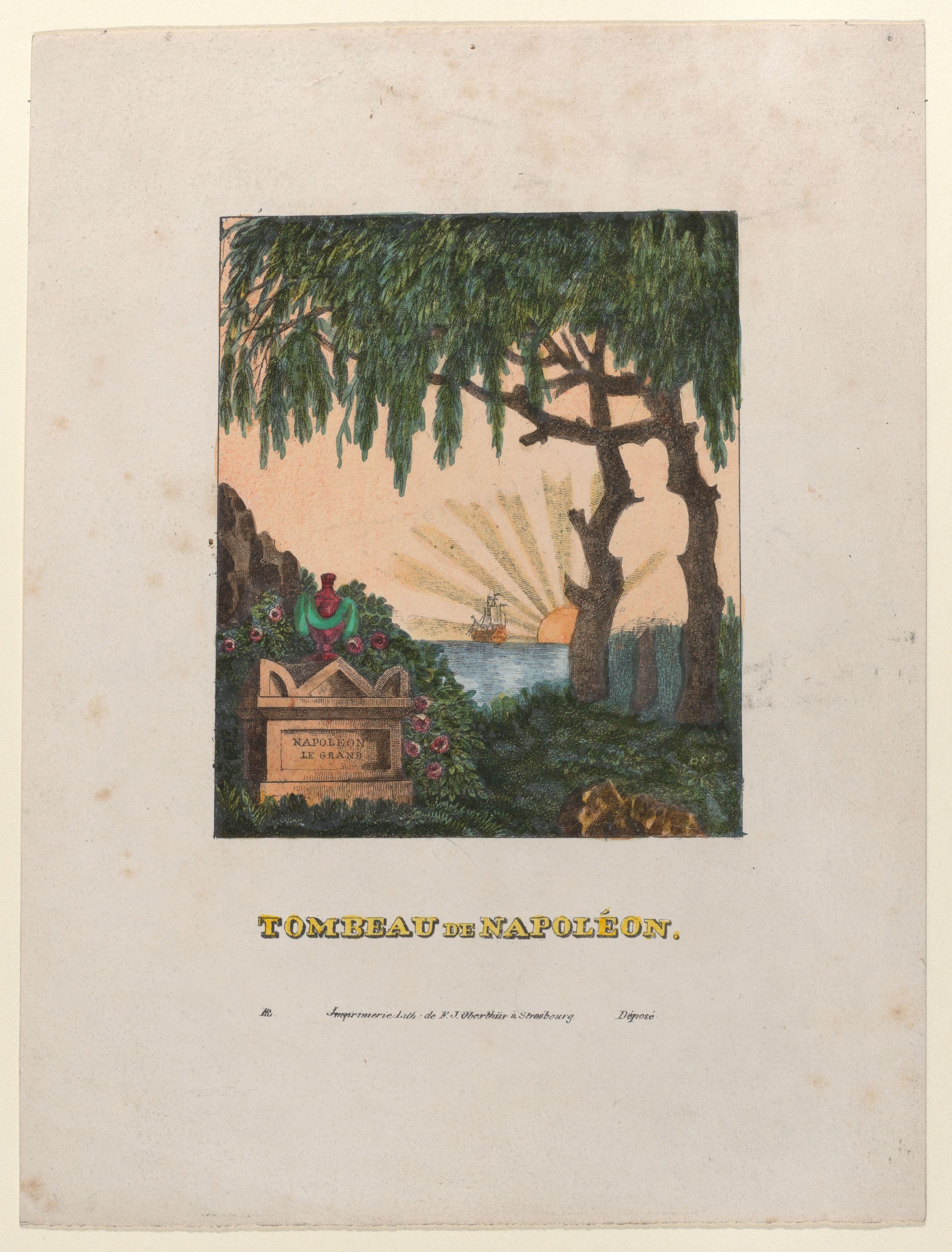

Napoleon's death in 1821 only served to enhance his mythic status. On the night that he died, a great storm raged over St. Helena, uprooting the willow at the chosen burial site. Following the funeral, Fanny Bertrand, the wife of a French general who had followed Napoleon into exile, took a number of slips from the uprooted willow to replant around the grave. Soon, any traveller who stopped at St. Helena, came to pay their respects—or gloat—at Napoleon's tomb (fig. 2). ‘The willows are objects of peculiar regard’, noted William Webster in 1830, ‘they are taken away piecemeal by every visitor, and are treasured like the relics of some holy shrine’ (Webster 1834: 357-8). Those who recorded their impressions would unfailingly pluck a sprig of willow, drink water from the spring and reflect on the transience of glory. So established was this convention that when HMS Beagle anchored at St. Helena in 1836, Charles Darwin simply noted in his journal: ‘After the volumes of eloquence which have poured forth on this subject, it is dangerous even to mention the tomb’ (Darwin 1846: 287).

To cater to the passing traffic, a brisk trade in willow mementoes sprang up on St. Helena. The caretaking couple at Napoleon's tomb cultivated a patch of willows ‘for the accommodation of such enthusiastic strangers as might wish to make themselves supremely happy by the purchase of such a SOUVENIR of their pilgrimage’ (Lockwood 1851: 81). Cheap and easily transportable, willow slips in water were a favourite tomb-side purchase. Willow trinkets also abounded. Travellers were offered ‘anything from a tooth-pick to a walking stick, with a perfect guarantee that they are all made of that wonderful willow which shaded Napoleon's grave’ (Brice 1901: 173).

The associations of the weeping willow made it peculiarly appropriate as an emblem for the deceased emperor. The tree's common name in a range of European languages identified the weeping willow with grief: saule pleureur, Trauerweide, salice piangente, Sauce Ilorón. The Linnaean name for the species, Salix babylonica, alluded to Psalm 137 and the lamentations of the captive Jews: ‘By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows’ (v. 1-2). The botanical name situated the tree within a biblical tradition of affliction and exile.

In nineteenth-century France and Germany, weeping willows were frequently planted in cemeteries. According to the French botanist, Jean Louis Marie Poiret, the swaying branches suggested 'soothing, though softly melancholy reflections' well suited for the graveyard; ‘its light and elegant foliage’ flowing ‘like the dishevelled hair and graceful drapery of a sculptured mourner over a sepulchral urn’ (Poiret 1829: 369; Loudon 1844: 1509). In Poiret's account, the living tree merged with memorial art.

But weeping willows were not only associated with grief and death. The ability of weeping willows to reproduce vegetatively—with twigs taking root to form new plants—meant that the tree also symbolised rebirth. In graveyards, as John Lundy observed in 1876, ‘willow trees droop their graceful branches ... in token of resurrection and future life’ (Lundy 1876: 424). Weeping willows expressed many of the qualities associated with Napoleon's final years and posthumous reputation: melancholy and exile, mourning and resurrection.

The ease of vegetative reproduction enabled the transfer and proliferation of the species. Napoleon willows abounded in nineteenth-century Britain. J. C. Loudon dated the first British import to 1823, observing that the fashion for Napoleon willows quickly took hold ‘and, in consequence, a great many cuttings have been imported, and a number of plants sold by the London nurserymen’ (Loudon, 1844: 1511). An early specimen displayed at Kew drew such crowds that the door to the botanic garden gave way in the crush. French visitors were known to kneel bareheaded before the tree to pay their respects (Smith, 1880: 261-2). The Napoleon willow continued as one of Kew's great attractions until it was felled in 1867; specimens of its wood remain in Kew's Economic Botanic Collection to this day (EBC 18093, EBC 25002).

In the decades succeeding the emperor's death, Napoleon willows made their way across the Atlantic. In 1835, a Napoleon willow was planted on George Washington's grave at Mount Vernon, in recognition of Bonaparte's admiration for Washington. From there, Napoleon willows spread to various locations across North America including New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Wisconsin, Virginia, San Francisco and Seattle.

For some—particularly British—commentators, the nineteenth-century Napoleon willow craze was a form of relic-hunting of questionable authenticity and dubious Catholic resonance. Charles Mackay, for instance, included the Napoleon willow in his Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions (Mackay, 1841: 165-6). For others, the charisma of the deceased emperor was such that the willows were legitimate objects of interest. In 1843, the entrepreneurial collector John Sainsbury, hired the Egyptian Hall on Piccadilly to mount a vast exhibition of Napoleonica. Attracting some 100,000 visitors, at half-crown apiece, the ‘Napoleon Museum’ included prints of the willow-shaded tomb and jewelled reliquaries containing willow fragments.

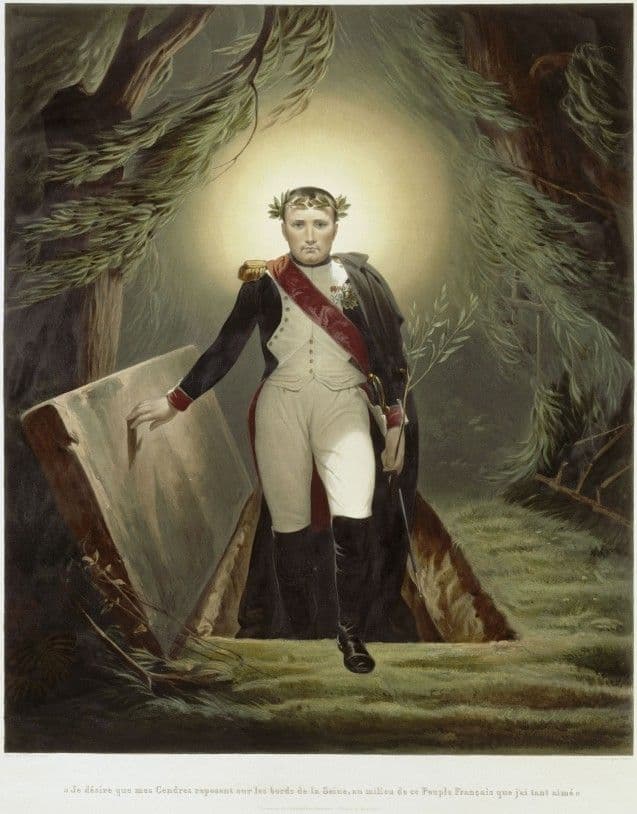

Items associated with Napoleon were, of course, even more potent in France. Under Bourbon rule (1814, 1815-30), censorship laws forbade written and verbal endorsements of the former emperor. Napoleonic supporters expressed their defiance through a range of material objects and images. Rumours of Napoleon's escape and return to France circulated regularly, even after his death. Poems and song reinforced the notion that Napoleon was not dead. Popular prints represented the shade of Napoleon visiting his tomb; the ghostly silhouette of the emperor at once revealed and concealed by the trunks of the willows (fig. 3).

In an attempt to lay the ghost of Napoleon finally to rest, the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe I (1830-48) negotiated with the British the return of Napoleon's remains to France, as requested in Napoleon's will. A French delegation, led by the Prince de Joinville, sailed to St Helena in 1840 to exhume Napoleon's body (which was found to be miraculously intact) for re-interment in Paris. The stumps of the willows at the grave were uprooted and divided as keepsakes amongst members of the party. To celebrate the return of the remains, the French engraver Jean-Pierre-Marie Jazet, issued an extraordinary print, depicting Napoleon rising Christ-like from his tomb. The illuminated, haloed figure was framed by wind-swept willow branches, recalling the storm that raged at Napoleon's death, a potent symbol of resurrection (fig. 4).

With our current questioning of imperial memorials and concern for the environment, it seems appropriate to broaden our understanding of modes of commemoration from statues to the natural world. No weeping willows adorn the site of Napoleon's tomb on St. Helena today. However, Napoleon willows survive in unlikely spots around the world: in the Scottish village of Ecclefechan (BBC News, 17.9.2018), on a neglected lot beside a freeway in Seattle (Lakitis 2018). Indeed, the entire stock of weeping willows in South Africa, Australia and New Zealand is said to have been descended from the trees on Napoleon's grave (‘Napoleon's Willow’, The Times, 5. 5. 1948). So easily does the species spread down watercourses, that Salix babylonica is now categorised as an Environmental Weed in Southern and Eastern Australia (Weeds of Australia) and an Invasive Alien Plant (Category 2) in South Africa (SANA). Through the unstoppable proliferation of weeping willows, Napoleon has managed to gain a new arboreal empire.

References

- Anon. (1825) Flora Sta. Helenica. St. Helena: J. Boyd.

- Anon. (1948) Napoleon's Willow. The Times, 5 May 1948, p. 5.

- BBC News (2018) Scotland's Tree of the Year Contenders Revealed. BBC News, online, 17 September 2018.

- Brice, A.M. (1901) St Helena: Old and New. Temple Bar 124: 173.

- Darwin, Charles (1846) Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of the Beagle Round the World under the Command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N., Vol. 1. New York: Harper and Brothers.

- Lakitis, Erik (2018) “It Has a Story to Tell’: How a Descendant of Napoleon's Willow Tree Took Root on a Seattle Hillside. Seattle Times, 29 October 2018.

- Lockwood, Joseph (1851) A Guide to St. Helena, Descriptive and Historical, with a Visit to Longwood, and Napoleon's Tomb (A Sketch of the History of the Island Saint Helena) (signed, J.L., i.e. J. Lockwood) MS. Notes. St. Helena, Ascension, and Tristan da Cunha.

- Loudon, John C. (1844) Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum: Or, The Trees and Shrubs of Britain, Vol. 3. London: The Author.

- Lundy, John P. (1876) Monumental Christianity, Or the Art and Symbolism of the Primitive Church as Witnesses and Teachers of the One Catholic Faith and Practice. New York: J.W. Bouton.

- Mackay, Charles (1841) Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions, Vol. 1. London: Richard Bently.

- McAleer, John (2016) “A Young Slip of Botany”: Botanical Networks, the South Atlantic, and Britain's Maritime Worlds, c.1790–1810. Journal of Global History 11: 24–43.

- Poiret, J. L. M. (1829) Histoire Philosophique, Littéraire, Économique des Plantes de L'Europe, Vol. 7. Paris: Ladrange et Verdière.

- SANA: South African Nursery Association (n.d.) Invasive Alien Plants. SANA: South African Nursery Association, online.

- Scurr, Ruth (2021) Napoleon: A Life in Gardens and Shadows. London: Chatto and Windus.

- Smith, John (1880) Records of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archives, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

- Webster, W. H. B (1834) Narrative of a Voyage to the Southern Atlantic Ocean, in the Years 1828, 29, 30, Performed in H. M. Sloop Chanticleer, Vol 1. London: Richard Bentley.

- Weeds of Australia (n.d.) Weeds of Australia, online.