Two late night taxi drives. The first was 20 years ago, in Beirut, and the taxi driver is listening to a song mourning the lost gardens of Granada; the next, perhaps 35 years from now, the taxi driver on the northern shoreline of central Florida is listening to a Latin melody lamenting the drowned gardens of Miami.

The story of lost gardens permeates many cultures; the expulsion from an Edenic state that lingers bittersweet in family stories and folklore. The expulsion from Eden, the expulsion from Granada in the 1500s, from Palestine in the 1970s, and from Havana ongoing since the 1950s -- all continue to resonate with melancholy stories of rusty keys, jasmine wreathed gardens, and beloved farms. The next chapter in this ancient lineage of legend is starting, as we prepare to mourn our lost gardens of the Anthropocene.

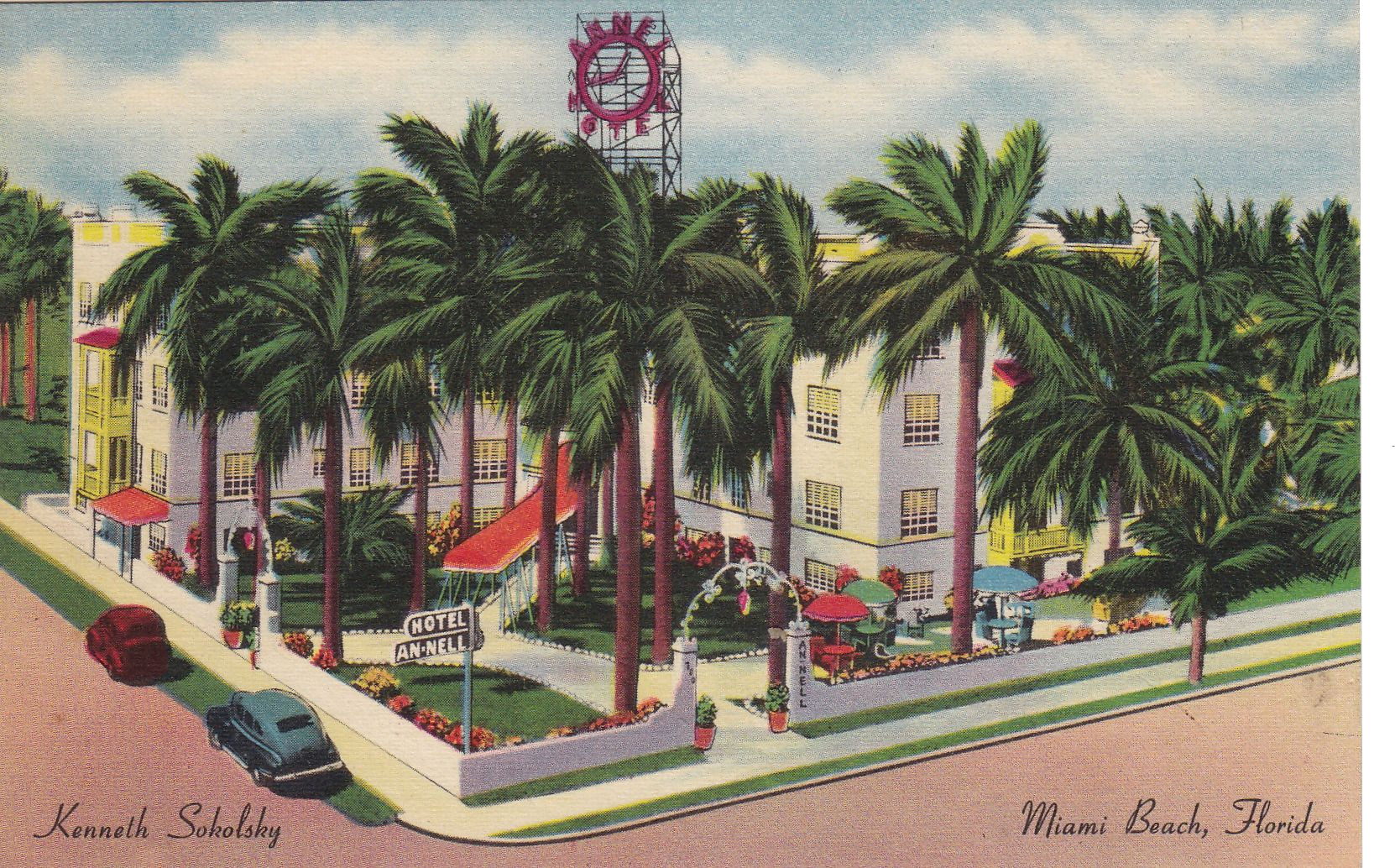

There is perhaps nowhere better than Miami to reflect on the golden age of gardens, where human wealth and a relatively stable climate created extraordinary landscapes and plant collections. Miami grew from the marsh, and it appears it could, after a moment of splendour, sink back into the mangrove and sea grass. In 1920 Miami was a small town, a trading station on the Miami River just about to undergo a spectacular real estate boom. It is now a sparkling, often beautiful city, perched on a ridge of sand between the equally blue planes of sea and sky.

Something special happened in Miami in the early 1900s, when a series of extraordinary individuals started creating gardens of a scale and beauty unparalleled in the US. Their fantasies were focussed on a stretch of limestone running north to south, known locally as the Miami Alps or the Miami Rock Ridge, a dizzy 15 feet above sea level. One area, once referred to as the Hunting Grounds, now called Coconut Grove, was the epicentre for these new gardens.

In 1916, the economic botanist David Fairchild bought a narrow piece of land on Biscayne Bay and started creating his garden, The Kampong (now part of the National Tropical Botanical Garden). A career plant hunter and economic botanist for the US government, he wanted a garden for his collection of favourite plants. The garden was filled with groves of avocado and mango, exotic flowering trees, and aromatic shrubs.

Further south, between 1913 and 1918, the wealthy Chicago industrialist Charles Deering was buying hundreds of acres of land to create his new estate. North of the Kampong, his brother James Deering was building his wonderfully exuberant Vizcaya estate. Both estates, although fundamentally different in style, had extensive new plantings of tropical fruit, exotics, and natives.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) established a series of plant germplasm collections, culminating in the founding in 1923 of the still extant Chapman Field. Today it is characterised by large plantings of mango and flowering trees, as well as the remains of David Fairchild's old chocolate growing houses.

The next big garden development followed the arrival of Colonel Robert Montgomery, a lawyer and pioneering accountant. Montgomery established the Coconut Grove Palmetum in 1932 and started accumulating one of the world's largest and most comprehensive palm and cycad collections. Now a global centre for palm and cycad conservation. Montgomery was drawn to Coconut Grove after reading the books of David Fairchild.

Fairchild and Montgomery soon became close friends and Montgomery proposed the creation of a new tropical botanic garden, appropriately named the Fairchild Tropical Garden (later the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden). Founded in 1938, it has grown into a world class tropical botanic garden.

Thus, by the 1940s, this narrow stretch of land contained an extraordinary cluster of important gardens. Although their status grew and contracted with the dynamics of Miami, these gardens enriched the landscapes of Miami-Dade. Today, you can walk down a road in Miami and spot 30 species of palm. In early summer, the city glows with the orange blossoms of the Poinciana tree (Delonix regia) introduced by David Fairchild. Every now and then a baobab (Adansonia sp.) emerges from a city landscape or museum plaza.

A strange synthetic tropical world had been created -- an ersatz jungle. Perhaps nowhere else in the world has so much exotic plant diversity been squeezed into a city and its agricultural hinterland. This perceived tropical paradise was further enriched by the increasing impact of Latin culture on Miami (within living memory Miami was a quiet and segregated southern city) and accentuated by the exotica released by animal dealers and pet owners (pythons in the Everglades, macaws nesting in the Royal Palms, and flamingo flocks at the Hialeah Race Course). No wonder Miami was the place for snow birds to escape the northern winter.

My family and I arrived in Miami in 2002. We made it home and relished the climate, the culture, and the biodiversity. Yet the signs of change were there. The city, and particularly the gardens, were still reeling from Hurricane Andrew in 1992. You could read the impact of that storm in Miami's trees -- twisted limbs, strangely leaning specimens, and shattered trunks that had regrown with straggly shoots. Later, I remember an orchid grower claiming that he could no longer grow high altitude Andean orchids without air conditioning because the winters were getting warmer. Another time, an old-school mango grower told me about shifting blossom and fruiting times. I also recall a conversation with a nurserymen who was watching saline intrusion poisoning his nursery and killing trees.

Other signs of the Anthropocene were also becoming evident. Waves of new diseases swept through the landscape. The latest being laurel wilt, a lethal fungus that kills avocado and wild bay trees, transmitted by a beetle. Since its arrival in 2003 in packing materials from Asia, laurel wilt disease has had a catastrophic effect on the native bay trees in the Everglades and has now spread to the commercial avocado plantations. The historical avocado collection planted by David Fairchild at The Kampong now needs regular injections of insecticide to ensure its survival. It is not unusual to see whole orchards standing dead and withered.

Perhaps the most striking expression of this change occurred during a conversation with a much respected and beloved donor to one of the Miami botanic gardens-- a woman who loved the garden but asked with characteristic candour, "tell me why I should fund your garden if it is going to be destroyed by sea level change?" At the time, Miami was largely ignoring the threat of climate change; after all, the city's economy was fuelled by property prices and tourism. Today, however, things are changing -- I get the feeling that Miamians live less under the sun and increasingly under the brooding threat of the next "big one," the catastrophic repeat of Andrew, or the succession of storm punches that will undermine house prices. In 2017, Miami voted for a new tax to fund resilience against flooding and storm surges, a $400 million bond issue.

Several times while working in Miami, I walked the gardens that I managed the day before a storm was due to hit. It is a strange sensation knowing that a garden you love will be profoundly different tomorrow. I would take lots of pictures, trying to burn the shapes of trees and the abundance of the plants into my memory. The next day, or whenever the storm had passed, you knew you would have to leave home with whatever complications may have ensued there and navigate through flooded roads and downed trees to get to the garden. The gate may or may not work and the security teams may be waiting to get safe access. My job was to walk the site to ensure there was safe access and to prepare an immediate status report for the garden trustees. Sometimes the garden was OK -- just lots of leaves gone and fragile plants bent; other times entire trees were down, there was damage to buildings, and no power. Next, the work started -- calling round to make sure all the staff were safe, establishing safe access and a communication HQ, identifying safety priorities and calling tree surgeons, engineers, electricians and crane operators. Did the emergency generator keep the DNA collection secure; are the library and herbarium OK; what about the nursery?

The tidy-up can take weeks or months. After Andrew, the recovery took years. At some point, trees and palms must be replanted. I remember the pleasure of getting new trees planted was dulled by a worry about how long they had to grow before the next storm. With each storm the historical continuity of the garden is eroded -- fewer memories survive, fewer old trees to signal the memories of the last sixty or seventy years. Each storm brings another round of exhausting fundraising to repair another set of damaged buildings or facilities. Each storm brings another set of traumatic memories for the horticultural staff, who have seen the collections they love shattered by tide and wind. At some point the board, bruised from successive storm events, may ask whether the garden should move to a safer site away from the sea. The gardens may move, fracturing the relationship with their communities and donors. At some point only the most rambunctious exotics will remain; thickets of Nypa palm will mark the old Montgomery estate, a twisted jungle of fig trees will envelop The Kampong. Thus, the gardens of Miami may slowly erode, and as the storms and tide continually pummel the city, somebody may remember the lost gardens of Miami, victims of the Anthropocene.

This is a future I don't want. I have had the privilege of seeing the trees my father and grandfather planted continue to grow. I work with organisations rooted in particular locations and specific communities where multi-generational relationships have developed; where people trust that those gardens, those trees, will be there in 50 or 100 years. All this is threatened by climate change. The next few years will dictate whether these glorious Miami gardens are lost to the Anthropocene, or whether they are survivors, defiant agents of change forging a better Anthropocene. I'm betting on the latter.