In the summer of 2021, as people briefly returned to old habits and routines after the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, a window onto the strange and unfamiliar world of seeds and fruit was opened up the John Hope Gateway at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

This exhibition was a remarkable exercise in capturing the minute detail of plant life by one of the world's leading microphotographers. Over a period of six months, Levon Biss worked alongside the RBGE's curatorial staff to examine their entire carpological collection, which amounts to around 3,500 specimens (Harris 2021). From this collection, Biss selected a hundred or so items to re-enliven under the microscopic lenses of his photographic rig, which takes thousands of photographs of the same object in order to produce an image that is fully focused from front to back (Biss 2021).

The result is a series of exquisitely detailed photographs that are equal parts strange, compelling, and enigmatic. Together with the accompanying exhibition text, which can still be read and enjoyed alongside the photographs in the book The Hidden Beauty of Seeds and Fruit: The Botanical Photography of Levon Biss (2021), they invite us into this most unfamiliar of worlds to share in a story of multispecies connectivity against the backdrop of multiple environmental crises. The exhibition and book also highlight the work being undertaken by the RBGE to combat these crises.

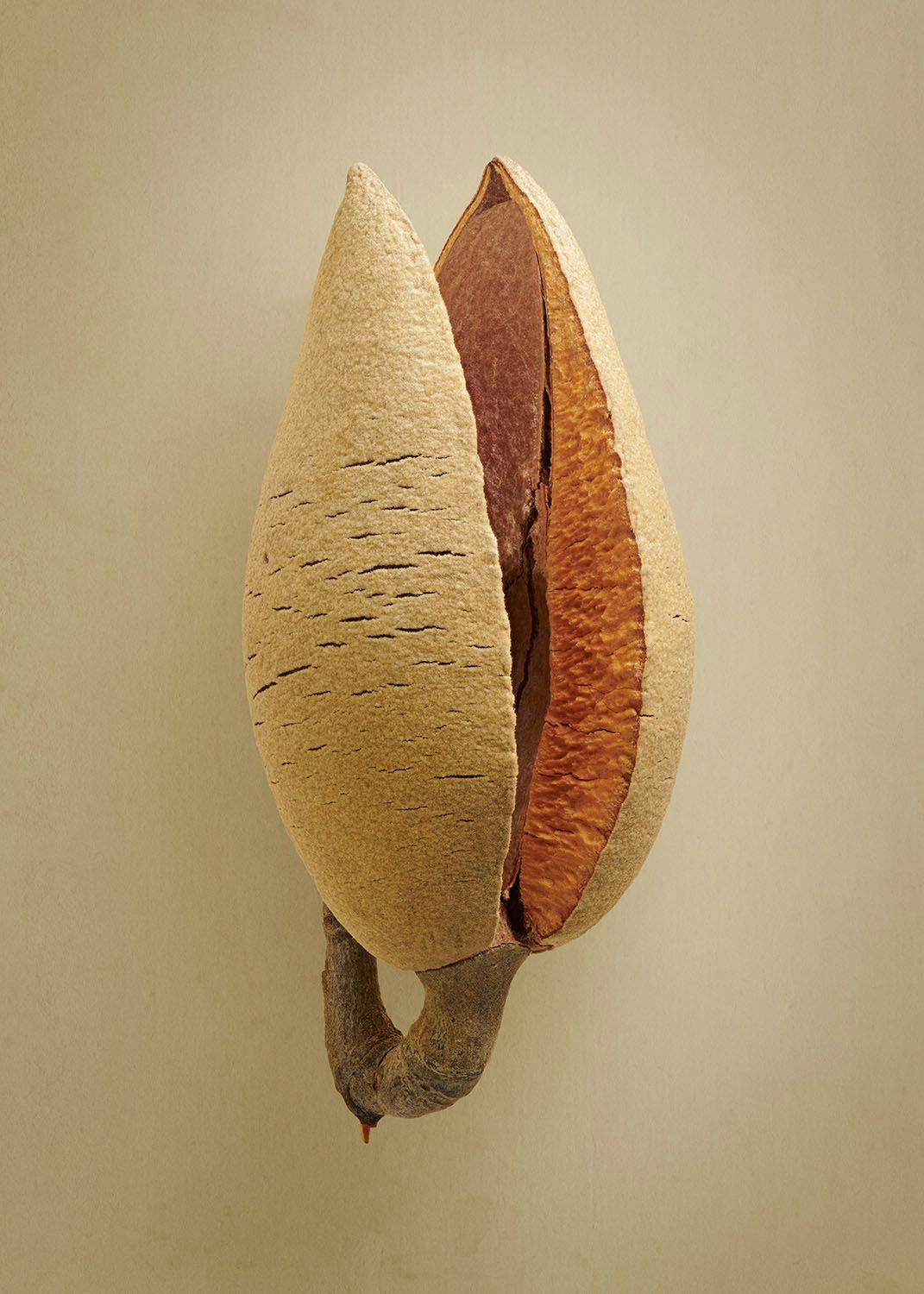

In one striking image, the seed and fruit of the melembu tree (Pterocymbium tinctorium Malvaceae) is brought to life by using a creative backlighting technique that creates an impression of an object that feels almost within our grasp. Biss seems to approach his compositions as a lighting designer might think about a stage set, using his carefully placed camera lenses to create a precision of form and a panoply of shadows and colour that generate depth, character and impact. Each image is accompanied by a short paragraph that provides a brief synthesis of descriptive, taxonomical, ecological, and anthropological information. The text accompanying this image, for example, informs us that the melembu tree is extremely tall and that its fruit is dispersed by the wind. The tree's bark is a source of fibre for making rope, and is also used in dyeing cloth (Biss 2021a).

Other specimens tell different stories. We are informed that the wax-leaved climber (Cryptolepis buchananii) is named krishna sariva in Sanskrit and karanta in Hindi, and that the RBGE is currently working with Nepali partners to build their capacity for in-country plant biodiversity research (Biss 2021a). Elsewhere in the exhibition, a short piece of text accompanying an image of the woody seed of the Medang pajai (Ternstroemia sp.) traces its scientific genealogy to the Swedish naturalist Christopher Ternstroem, pupil of the famed taxonomist Carl Linnaeus. We learn that the wood of this genus is used for light construction, while the bark is used to produce fish poison. The colourful seed, which appears somewhat dulled in the photograph due to the specimen's drying process, is said to be distributed by birds, who are attracted to its vibrant shade of red (ibid.).

The images and their accompanying text afford a glimpse into the realm of multispecies agency, in which birds and other animals act alongside humans and plants to create a world in which these seeds and fruit are active and lively participants. Speaking at an event held as part of the Edinburgh Science Festival, Biss (2021c) described microphotography as a different way of thinking. This exhibition, with its striking fusion of facts and stunning imagery that brought to life our entangled, threatened worlds, proved an effective vehicle for encouraging people to think differently about plants.

Walking around the exhibition space, I was reminded of the work of Natasha Myers, an anthropologist and director of the Plant Research Laboratory. Myers has recently called on us to reconsider our relationship with plants, urging us to repeat the mantra: "We are not alone" (Myers 2021). This is one of the first steps in her ten-step guide to life in the Planthroposcene, a manifesto and self-described incantation, or an attempt to "conjure other worlds within this world" (ibid.). In this guide, she argues that we should "vegetalise our sensorium" and "disrupt colonial common sense" in order to push for another way of living with and alongside plants in an argument that might bring to mind Donna Haraway's (2016) call for more-than-human kinship in the face of spiralling environmental devastation.

Her final step, however, is to call on us to make art for this epistemological experiment by refusing the aesthetics of ruination. Focusing on images of ecological ruin "constrains our imaginations about wild growth to sites of cultural decay", she argues, "as if it is only in the wake of human extinction that plants will be able to express their full, unfettered (read: monstrous) powers" (Myers 2021). Instead, she asks us to cultivate a taste for art that stages "intimate relations between plants and people" (ibid.). This is precisely what Biss achieves so effectively in his photography. Through his skilful use of lighting, he succeeds in bringing these specimens to life, picking up detail, casting light and shadow in a way that draws us into an image in much the same way as we might be drawn to portraiture. We are able to look at these images and imagine them looking back at us.

In an interview with The Ethnobotanical Assembly, Myers remarked that: "I think huge political change is possible with the simple work of learning how to transform how we regard plants and shape our relationships with them. Plants are already at the centre of our economies. Imagine what could happen if we redesigned our worlds to be of service to them?" (Lomeña 2020). This is the radical potential of an exhibition such as this one. I felt both inspired and intrigued by the stories told in this exhibition, and the questions raised during my visit have stayed with me.

The RBGE curator David Harris (2021b) notes in his foreword to the book accompanying the exhibition that he was unsure whether Biss would be able to find enough colour in the carpological specimens to make for an interesting study. There was no need for concern—colour abounds in these photographs and in the stories that accompany them. The exhibition has been beautifully preserved in the pages of a hardback book, in which plentiful space has been given to both images and text. You will wonder at the detail in the photographs and find yourself becoming lost in the stories that they tell. You will want to find out more. And maybe, just maybe, you will be inspired to think again about the plants in your life and your relationship with them.

References

- Biss, L. (2021a) The Hidden Beauty of Seeds and Fruit: The Botanical Photography of Levon Biss. 28th of August to 26th of September 2021. Edinburgh: Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

- Biss, L. (2021b) The Hidden Beauty of Seeds and Fruit: The Botanical Photography of Levon Biss. New York: Abrams.

- Biss, L. (2021c) In Conversation with Levon Biss. Edinburgh Science Festival. Online talk, 1 July 2021.

- Haraway, D. (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Harris, D. (2021) Foreword. Inn The Hidden Beauty of Seeds and Fruit: The Botanical Photography of Levon Biss. New York: Abrams.

- Harris, D. (2021) In Conversation with Levon Biss. Edinburgh Science Festival. Online talk, 1 July 2021.

- Lomeña, A. (2020) Seeding Planthropocenes: An Interview with Natasha Myers. The Ethnobotanical Assembly, Issue 6: Autumn 2020.

- Myers, N. (2021) How to Grow Liveable Worlds: Ten (Not-So-Easy) Steps for Life in the Planthroposcene. ABC Religion and Ethics, 7 January 2021.