At first glance, the herbarium at Kew appears vast and still, almost cathedral-like, where corridors of tall cabinets hold innumerable dried leaves, seeds, flowers and stems attached to sheets of paper within folders. These sheets are scientifically valuable specimens which constitute an almost infinite reservoir of plant knowledge. Yet far from being static pages, they contain evidence not only of the hours of fieldwork by collectors scattered across the world, but also the ways in which the knowledge of botanists and taxonomists has evolved from the point of first taxonomic classification to the most recent plant that has been collected. Information on the earliest labels, stamps and notations is complimented by analysis of the specimens themselves, enabling botanists to classify and name plants accurately. As Kew Gardens' ethnobotanist William Milliken puts it: ‘An accurately named plant opens the doors to a wealth of information: its distribution, its uses and its ecology. Effective conservation, sustainable use of natural resources, climate change adaptation, ecosystem restoration—all are dependent on this ability.’1

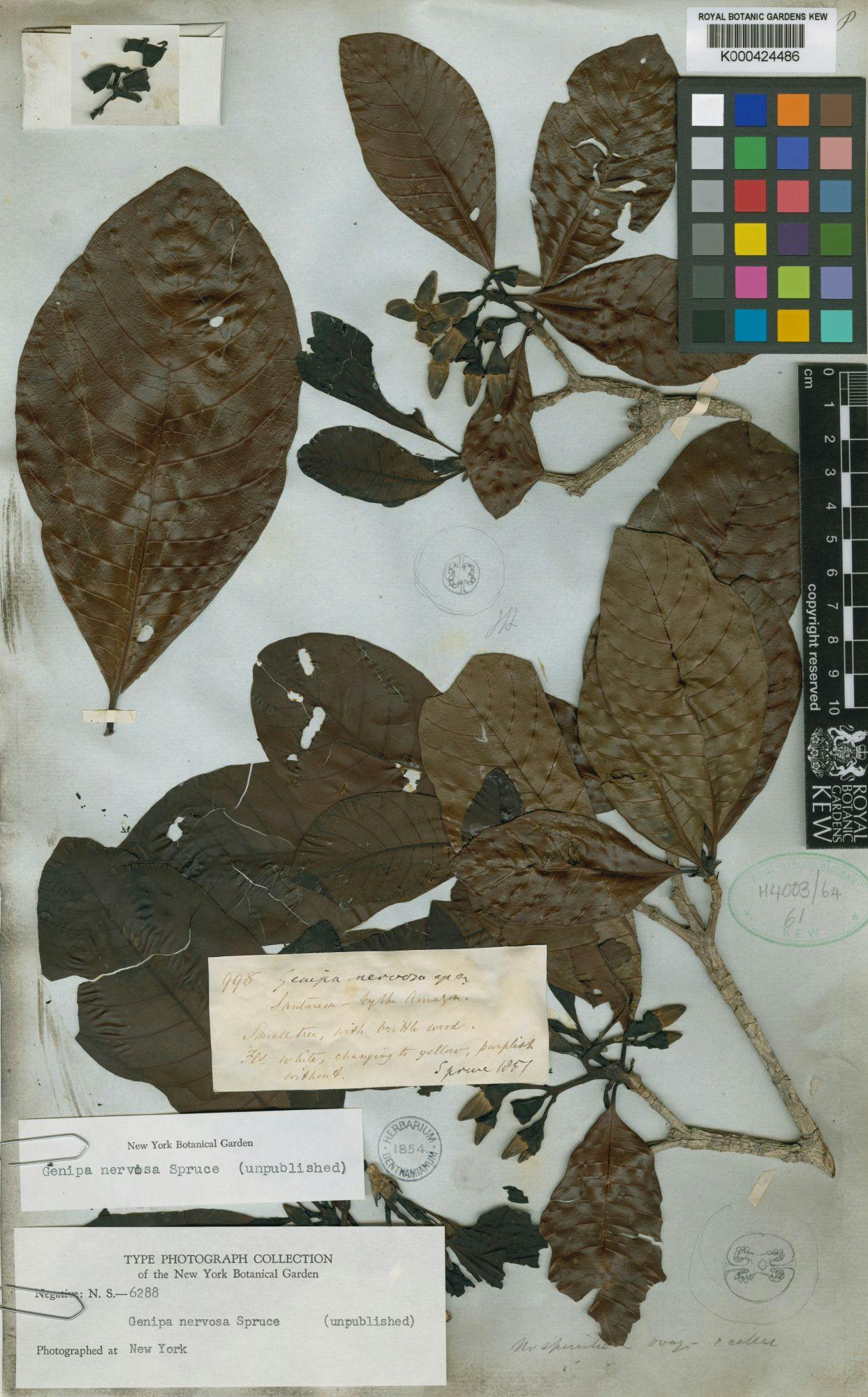

The herbarium sheet of Genipa americana collected by the botanist Richard Spruce is a case in point (fig. 2). One of the 14,000 specimens that he amassed during his 15-year journey to the Amazon and the Andes in the mid-nineteenth century, the herbarium sheet exemplifies his meticulous botanical work. The yellowed label, very likely attached to the sheet by Spruce himself, includes the collector number, ‘998’, the name of the specimen, ‘Genipa nervosa spr.’, the place where it was collected, ‘Santarem—by the Amazon’, and a short description of the plant: ‘Small tree, with brittle wood. F^ls^white, changing to yellow, purplish within it.’ The label is signed and dated, ‘Spruce 1851’. A small envelope on the left-hand side holds a few seeds, while pencil sketches (also very likely by Spruce's hand) show sections of a fruit, with a description of its morphology - ‘[?], ovary and celled’. A small black stamp reads ‘Herbarium Benthamianum 1854’, indicating that it formed part of George Bentham's herbarium of more than 100,000 specimens, which was donated to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in 1854. A green Kew stamp frames another reference number in pencil, a record of its loan to another herbarium in 1964,and two further labels (more recent, to judge by the whiteness of the paper) from the New York Botanical Garden state that the name ‘Genipa nervosa Spruce’ is ‘unpublished’. This means that it was a provisional name, identified by subsequent taxonomists as Genipa americana (Zappi et al. 1995). The label at the bottom includes the number of a negative, stating that the specimen was photographed in New York. On the top right-hand side, yet another label displaying a ‘Royal Botanic Gardens Kew’ barcode links this specimen with Kew's electronic catalogue, informing us that it has been digitised. Together these signs tell us something important about the function of the herbarium as a botanical institution, as well as its dynamism: for on these sheets of paper lie multiple stories about the mobility of specimens and the forms of knowledge connected with them.

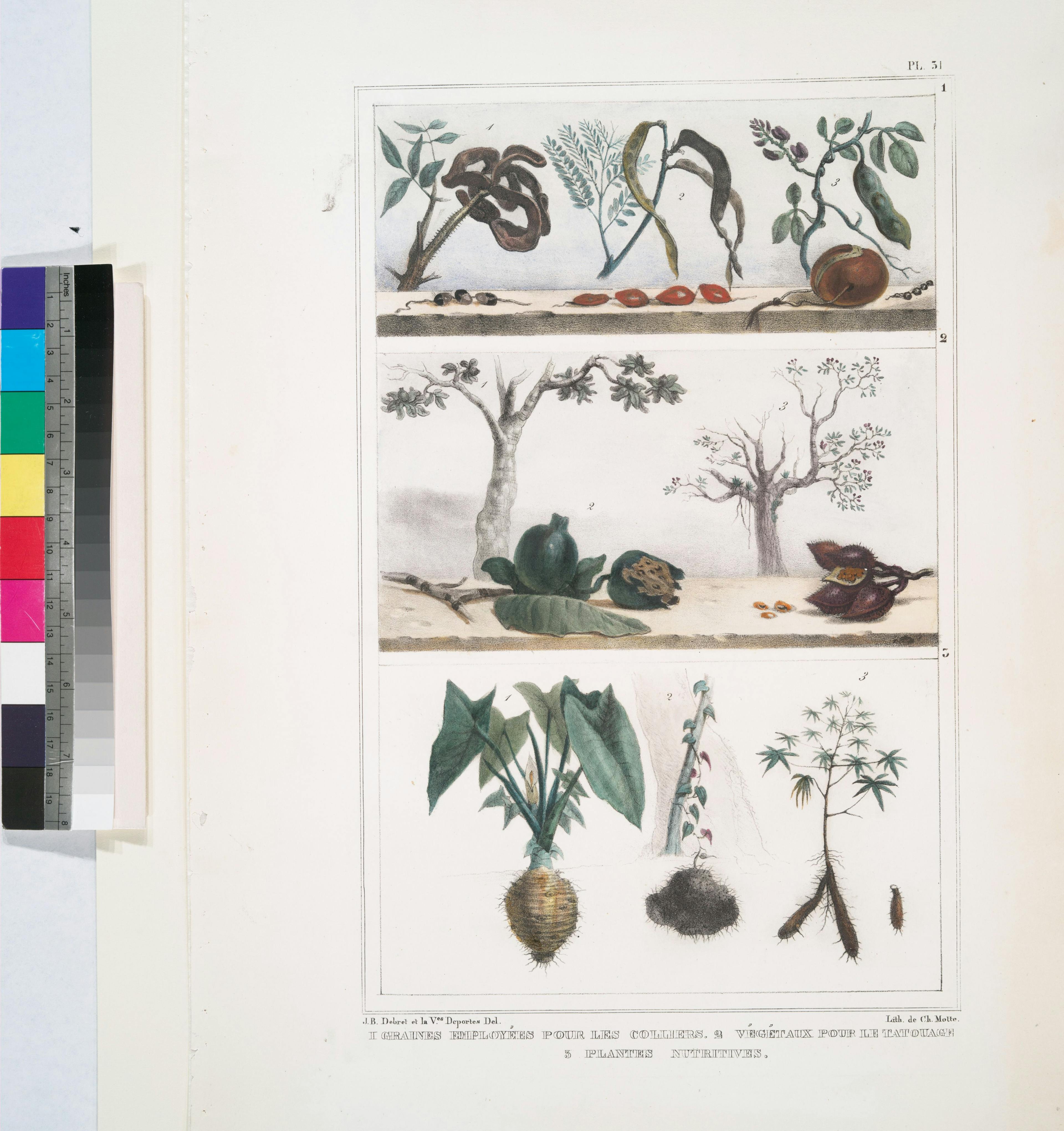

But herbarium sheets tell just part of these stories: Spruce materials held at Kew's Library and Archives are helpful for tracing the trajectories of these plants further. To continue the story of Genipa americana, in volume 1 of Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and Andes, a collection of Richard Spruce's travel journals and correspondence organised posthumously by Alfred Russel Wallace, Spruce states, the ‘Yenipápa’ fruit ‘(a large olive-green berry) affords a permanent black dye, and is in universal use by the Indians for staining their skins; it is also pleasant eating, when allowed to become over-ripe, having then the consistence and much of the flavour of the medlar’ (Spruce 1908: 164). In a manuscript journal listing useful plants from the Amazon, Spruce provided further information under ‘Genipa americana L.’, stating that ‘Genipápa’ refers to ‘Juice of fruit a black dye with which Indians paint themselves. Wood used for gunstocks and spoons.’2 In fact, together with the annatto bush(Bixa orellana), whose seeds yield a red-orange dye, Genipa americana's use by Indigenous peoples as a dye has been known by Europeans from the early days of colonisation of Brazil (Eder 2013: 99). These dye plants have been sources of inspiration as well as botanical knowledge to a myriad of artists and naturalists. Both plants are depicted at the centre of Plate 31 of Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil by the French artist Jean-Baptiste Debret (Debret 1834) (fig. 3). The accompanying text in this volume details the decorative and medicinal uses of the plants. On the delicately coloured lithograph by Charles Motte, from a drawing by Debret and the Viscountess de Portes, the fruits in the foreground are accompanied by the trees in the background, bringing the plant closer to life than the dried and pressed herbarium specimen.

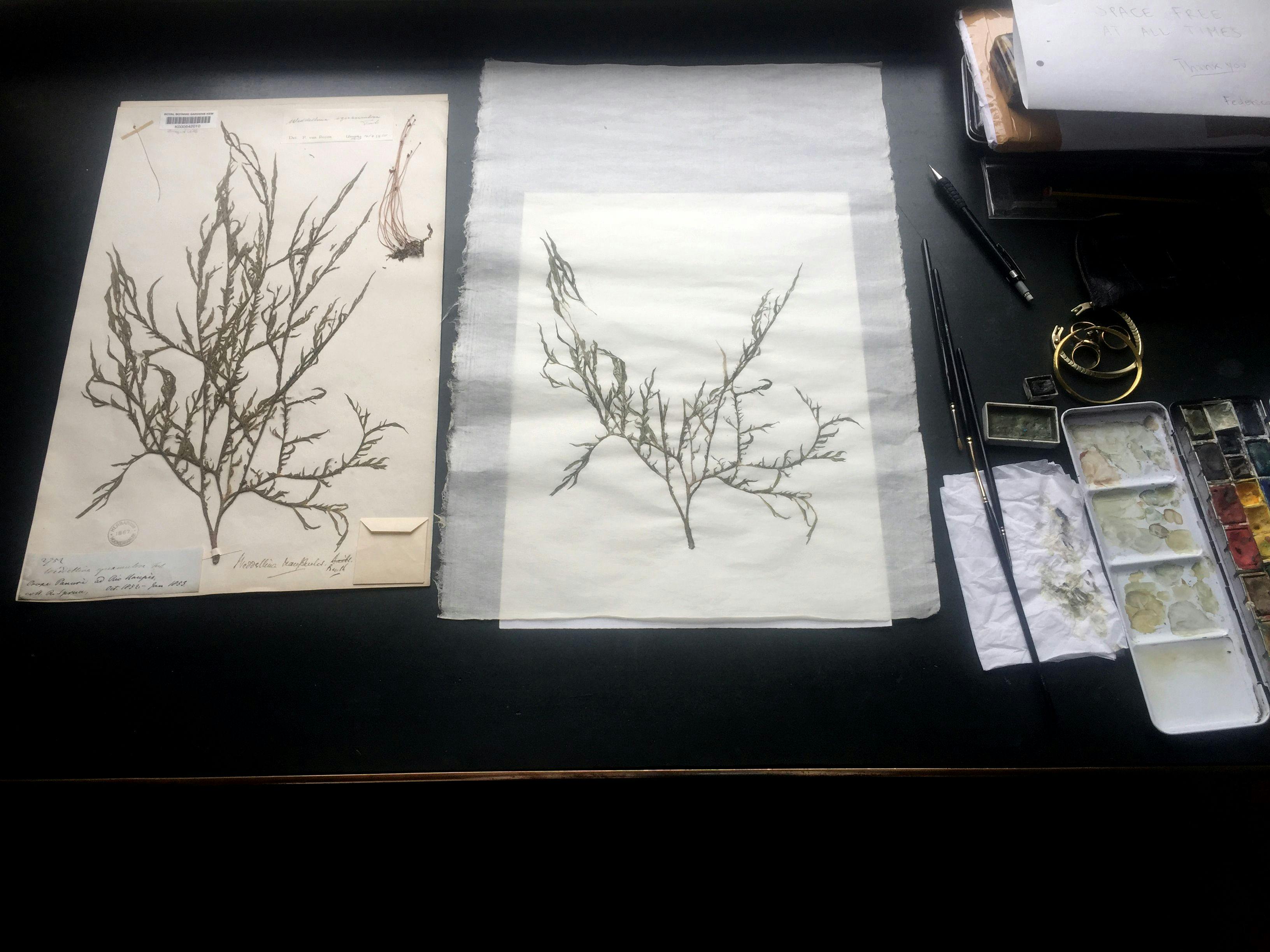

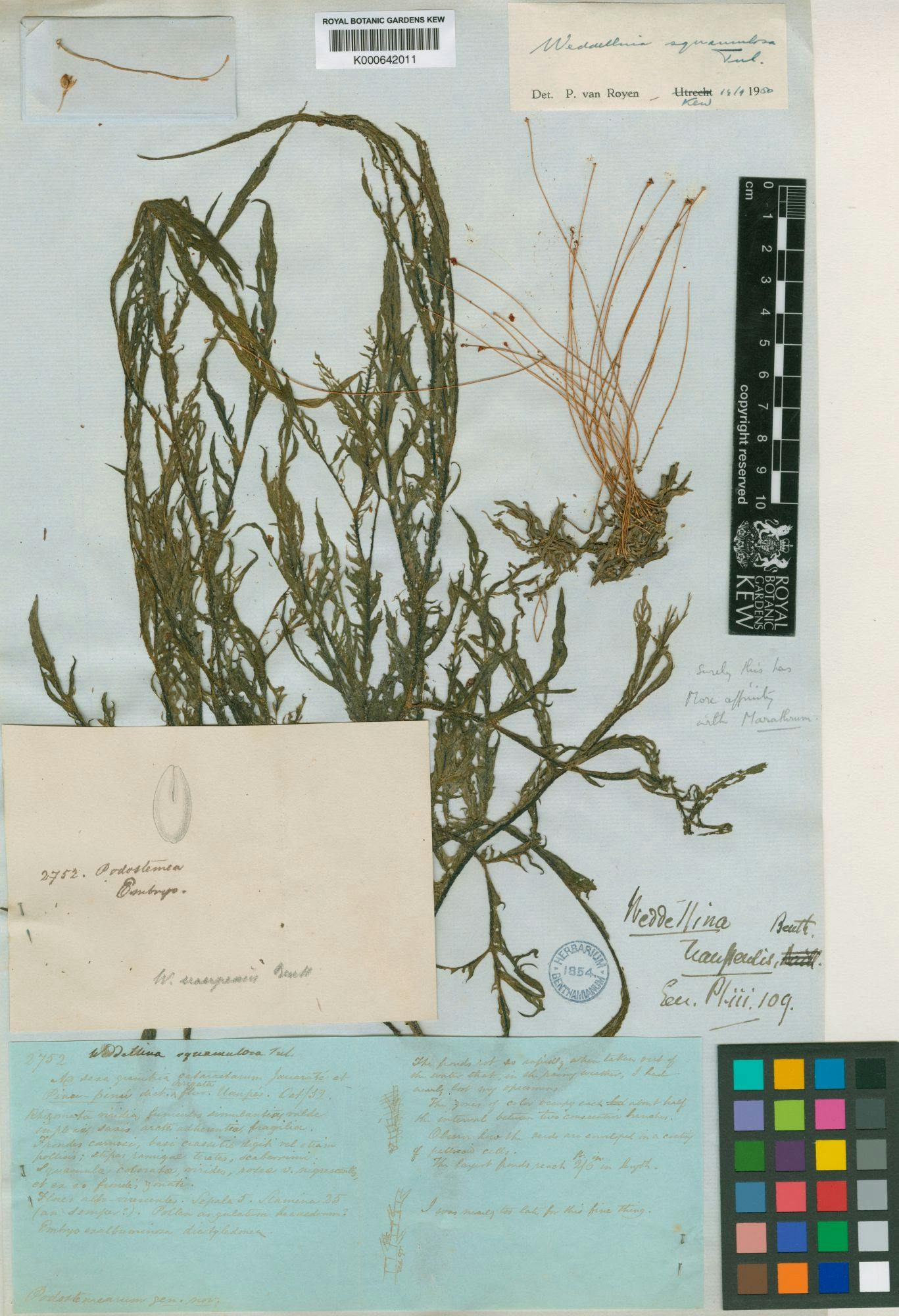

What happens then when a contemporary artist, such as co-author Lindsay Sekulowicz, interrupts the usual process of drawing from nature, by using the herbarium specimens collected by Richard Spruce in the Brazilian Amazon as stimulus for her art rather than seeking to depict the living plant in its natural habitat?3 What leads her to spend painstaking hours retracing a specimen of Podostemaceae (Weddellina squamulosa; fig. 4), for example? This is a weed from the river Uaupés collected by Spruce in October 1852. One label, attached precariously to the herbarium sheet with dressmakers' pins, reads ‘The fronds rot so rapidly when taken out of the water that, in the rainy weather, I had nearly lost my specimens’, positioning beside a small sketch, ‘I was nearly too late for this fine thing’ (fig. 5). For Sekulowicz, these notes reanimate specimens, bringing together the hands and eyes of the collector, the botanist and the artist.

By exploring alternative possibilities offered by the herbarium sheets, Sekulowicz also renders the herbarium as a workshop for her practice as an artist. For example, she recycles discarded herbarium folders into surfaces for her work. Their pastel hues have also provided the colourway for an educational board game inspired by Spruce's collection of biocultural artefacts in the North-West Amazon (fig. 1), bringing to the fore the materiality required by its subject matter. The board game, entitled A'pe-Buese (‘to learn playing’, in the Tukano language), forms part of a teaching and learning toolkit based on Spruce's collections recently developed for the use of schools in the upper Rio Negro in northwest Amazonia (Martins et al. 2021a & 2021b). In this board game, the artefacts have been depicted alongside their constituent raw materials, placed in relevant habitats, to be used as ritual instruments and tools by contemporary Indigenous peoples. In this way, A'pe-Buese subtly brings the past into the present, and returns the herbarium to the forest.

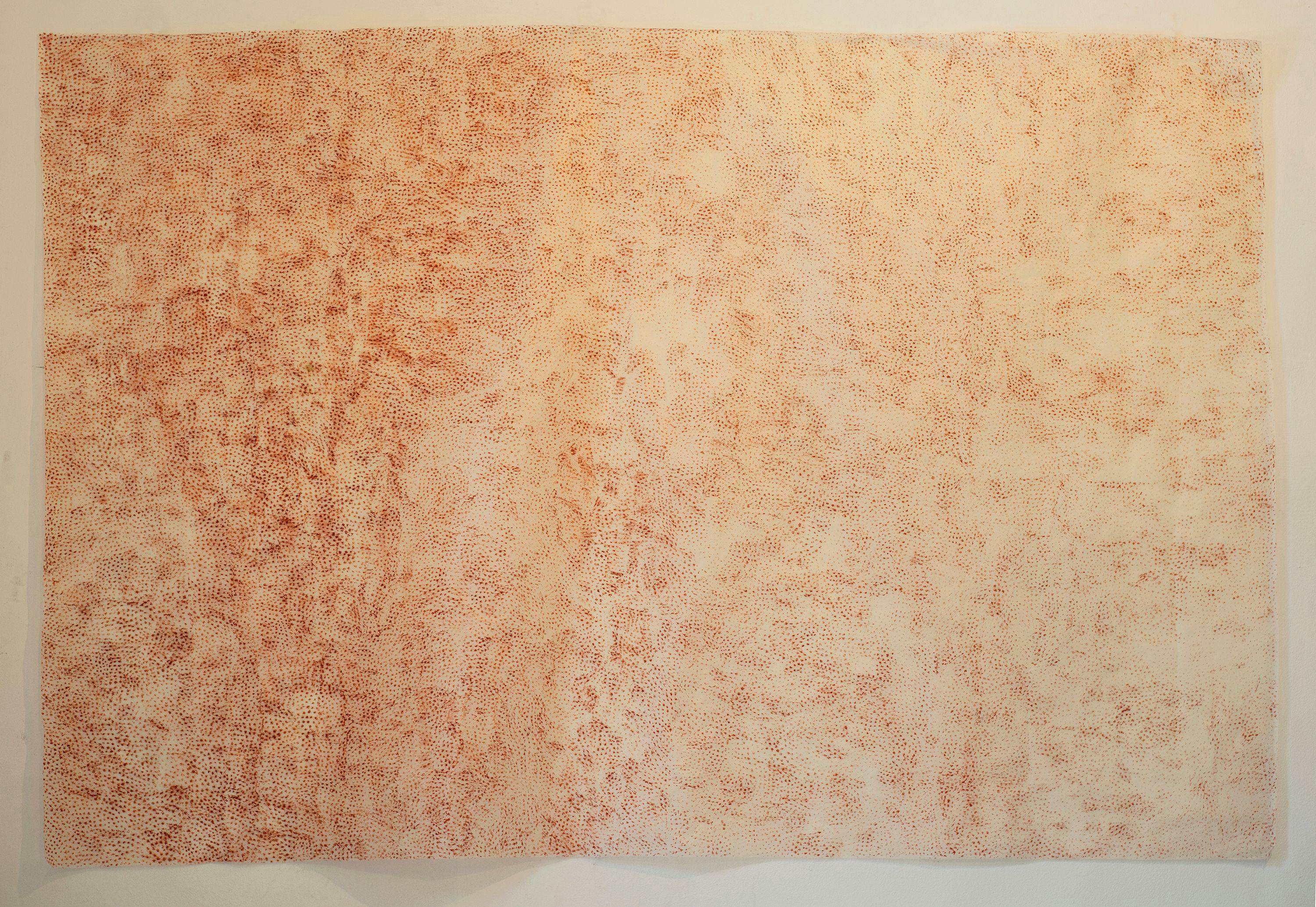

Sekulowicz's engagement with the Spruce collections goes beyond pictorial representation. Having managed to acquire fresh samples of jenipapo and annatto fruits, she quickly started experimenting with them, led by co-author Luciana Martins' researches on the use of these dye plants as evidenced in Kew's Library and Archives. By replicating the use descriptions provided by Indigenous women as documented in Spruce's manuscripts, the materials became a toolkit guiding the recreation of knowledge through making. At one point during this remaking process, Sekulowicz covered her hands in the fruit of jenipapo, eagerly awaiting the oxidisation process that would turn them the ubiquitous blue of the Indigenous peoples in South America. Discovering the fruit to be overripe, she nevertheless utilised the pungent juice by mixing it with charcoal from field horsetail (Equisetum arvense, a silica rich plant used to approximate the role of caraipé, Leptobalanus octandrus; fig. 6), painting this onto fragile unfired vessels she made with clay dug from riverbeds (figs. 7 & 8). In another work, she used the powder coating from annatto seeds to pattern a sheet of thin Japanese paper, making its surface vibrate with red hues (fig. 9).4 The annatto dye was found to be very unstable and quickly lost its intensity, eventually disappearing completely under bright light.

Sekulowicz's artistic practice is shaped by ideas about ritual through making, the circular nature of existence, and the fleeting nature of objects. Through her creative engagement with plant specimens and artefacts, the herbarium is transformed from botanical archive to workshop, a space for collaborative knowledge making. Working in this space means being open not just to the accretion of botanical knowledge over time but also to parallel fields of understanding that span diverse disciplines, geographies, histories and beliefs. Here may lie the specific value of artistic intervention, bringing to our attention different ways of seeing and experiencing the world and herbaria. Sekulowicz's body of work invites us to consider both what the Kew herbarium presents to the eye and how its mode of operation depends on knowledge systems beyond its particular brief. It takes us beyond the taxonomic concerns of botanical science into other ways of knowing the world of plants and peoples.

References

- Debret, Jean-Baptiste (1834) Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil, Vol. 1. Paris: Firmin Didot Frères.

- Eder, Flávio Coelho (2013) Plantas Nativas do Brasil nas Farmacopeias Portuguesas e Europeias, Séculos XVII-XVIII. In Usos e Circulação de Plantas no Brasil, Séculos XVI-XIX, edited by L. Kury. Rio de Janeiro: Andrea Jakobsson Estúdio Editorial.

- Martins, L., V.F-Kruel, A. Cabalzar, D.L. Azevedo, W. Milliken, M. Nesbitt, and A. Scholz (2021b) A Maloca entre Artefatos e Plantas: Guia da Coleção Rio Negro de Richard Spruce em Londres. São Paulo: Instituto Socioambiental.

- Martins, L., V.F-Kruel, L. Sekulowicz, M.E.R. Neves, and D.L. Azevedo (2021a) A'pe-Buese – Aprender Brincando. São Paulo: Instituto Socioambiental.

- Spruce, Richard (1908) Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and Andes. Edited and Condensed by Alfred Russel Wallace. London: MacMillan and Co.

- Zappi, D.C., J. Semir and N.I. Pierozzi (1995) Genipa infundibuliformis sp. nov. and Notes on Genipa americana (Rubiaceae). Kew Bulletin 50: 761–71. N.b. Thanks to William Milliken for this information.

Footnotes

-

William Milliken, ‘What’s in a collection? The Herbarium at Kew’ ↩

-

Richard Spruce, ‘Journals and uses of Amazon plants (mss II)’, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew Archives, Richard Spruce papers RSP/1/3, c. 1850s. ↩

-

Lindsay Sekulowicz’s work reflects the increasing interest in herbaria amongst contemporary artists, such as Alberto Baraya, Joanne B Kaar and Mark Dion (see Maura Flannery’s blogs in ‘Herbarium World: Exploring herbaria and their importance’). ↩

-

See ‘Plantae Amazonicae’ ↩