In 1967, a landmark symposium entitled Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs, was held in San Francisco at what was then the San Francisco Medical Center (Now UCSF) under the sponsorship of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Its purpose was to review the state of research at the time in the field of ethnopharmacology, with respect to the discovery and documentation of psychoactive plants or fungi used within indigenous cultures. Most of the leading researchers in this rather specialized field presented at this private conference, and new significant discoveries were discussed among the distinguished faculty. The only benefit afforded to the public (who, as taxpayers, had underwritten the costs of the event) was the publication of the symposium proceedings in a volume with the same name as the conference. This could be ordered for a time from the U.S. Government Printing Office as U.S. Public Health Service Publication #1645, but eventually went out of print. Originally, the intention was to stage follow up symposia about every ten years, but politics and the War on Drugs intervened and no additional conferences were ever held.

In the 50 years that have passed since, the field has continued, by and large with little or no funding from the usual sources of research support, and additional discoveries have been made. Some, but not all, have been published in peer-reviewed journals, but none have been collected into a similar volume. I don't remember how the first Symposium volume came into my hands at the age of 17 in 1968, but its contents and contributors significantly influenced my decision to seek a career in ethnopharmacology. In early 2017, a concatenation of serendipitous circumstances created an opportunity to organize a 50 th anniversary commemorative symposium, which we called ESPD50. The event was successfully staged at Tyringham Hall, a beautiful 18 th century country house in Buckinghamshire, UK, in June of 2017. In 2018, Synergetic Press published the 2017 Symposium proceedings along with a high-resolution reprint of the original 1967 symposium as a dual-volume, collector's quality boxed set. Although the 2017 Symposium was also private (this time funded through donations and not taxpayers) through the magic of live-streaming over 70,000 people were able to observe the presentations in real time from every part of the globe 1 . This option was not available in 1967, but it attests to the widespread interest in this topic and to the continued viability of the field of ethnopharmacology.

Although originally my intention for the symposium was to focus on more obscure and poorly investigated aspects of psycho-ethnopharmacology, as I reviewed the topics suggested by eventual participants and others, it became clear that there remained many unanswered questions, even with respect to plants and ethnomedicines that were considered well-investigated. For example, over the last 50 years and particularly in the last 30, ayahuasca, the now-famous Amazonian hallucinogenic brew, has been the subject of numerous ethnographic, ethnobotanical, and pharmacological investigations. So much new information has surfaced in recent decades that an entire morning was devoted to ayahuasca, and topics were presented that had never before been discussed in a symposium of this kind. Similarly, peyote has been scientifically investigated for well over 100 years; yet presenters at the ESPD50 symposium discussed historical and ethnographic aspects of peyote never before presented in public.

But, true to its original intent, the Symposium did include presentations on some of the lesser known areas of psycho-ethnopharmacology. An Australian investigator, Snu Voogelbriender, presented an ethnobotanical and phytochemical survey of the many hallucinogenic Acacia species. As a group, the species of this large genus include some of the most potent sources of DMT (dimethyltryptamine) and 5-Methoxy-dimethyltryptamine (5MeO-DMT) so far identified. Though most are native to Australia, others are found in Africa and a few in North America. Surprisingly, there is no documented evidence that the Australian Acacias were ever utilized by the Aboriginal people of Australia, although their art is certainly suggestive of altered states characteristic of DMT intoxication.

The conference also included presentations on Sceletium spp., (Kanna, among other names), a genus of the Azioaceae whose roots are consumed as a euphoriant, stimulant, anxiolytic and 'social lubricant' by the San people of the Kalahari. Dr. Nigel Gericke, a South African physician who presented the paper, has undertaken extensive ethnobotanical, phytochemical, pharmacologicial, and clinical investigations of the plant and its alkaloids, and has developed a standardized extract as a commercial dietary supplement, Zembrin ® ; both folk use and clinical studies support its use as an anxiolytic, antidepressant, and cognition enhancer. His work is an excellent example of how an indigenous psychoactive medicine can be ethically developed for commercial markets while preserving traditional knowledge and providing reciprocity, in the form of economic benefits, for the indigenous people who oversee its cultivation, harvesting, and manufacture.

Another investigator, Dr. Christopher McCurdy of the Department of Medicinal Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, University of Florida, presented on Mitragyna speciosa, or Kratom (Rubiaceae). This species is utilized like opium and sometimes as a substitute for opium, in Thailand and other Southeast Asian countries. The terpene indole alkaloids of Mitragyna, particularly Mitragynine and 7-Hydroxy-mitragynine, are potent agonists at µ opiate receptors (MOR), and also interact to a lesser extent with 𝜿 (KOR) and 𝛅 (DOR) receptors. Interestingly, although Mitragyna alkaloids have comparable or even greater potency than morphine at MOR, they also interrupt morphine dependency in animal models, and may have potential in treating opiate dependence syndromes. Unlike the opium alkaloids, the Mitragyna alkaloids and Kratom do not cause significant respiratory depression, which is the cause of death in most cases of opiate overdose. Thus these alkaloids may represent the Holy Grail long sought by opiate pharmacologists: A relatively non-toxic, and non-lethal opiate that nevertheless has the desirable analgesic actions that are the basis of the therapeutic effects of opium alkaloids.

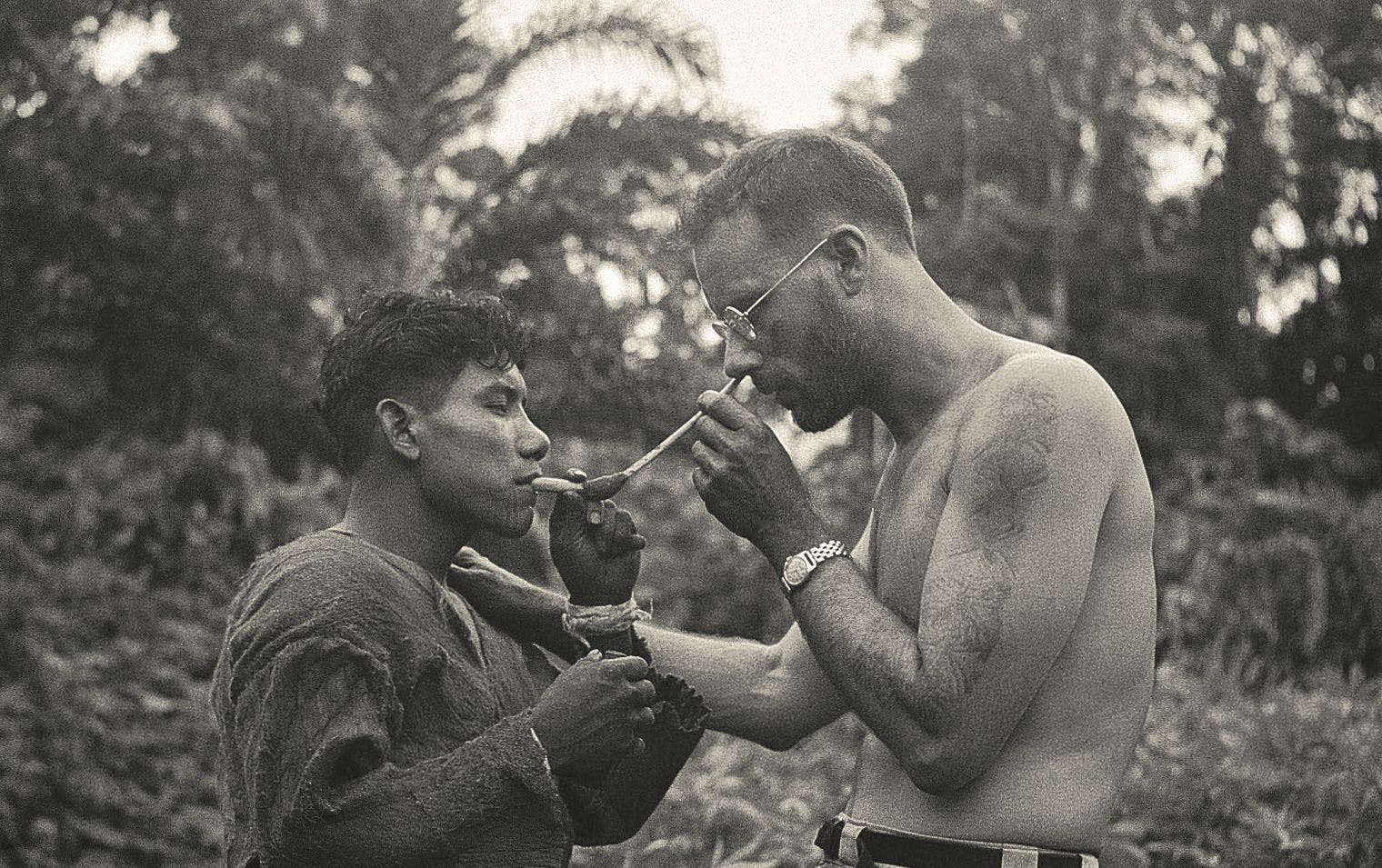

These are just a few highlights of the topics covered in the three-day conference and reported in the Volume II of the ESPD50 Symposium Volume. Other presentations included a historical retrospective on the Amazonian explorations of Richard Evans Schultes, the Harvard ethnobotanist now famous for his work on Amazonian hallucinogens. The paper was co-authored by ethnobotanists Mark Plotkin, Wade Davis and Brian Hettler. Dr. David E. Nichols, widely considered the world authority on the chemistry and pharmacology of psychedelic agents, gave a Keynote address on the contributions of psychedelic natural products to medicinal chemistry. Dr. Jeanmare Molina of Long Island University gave an interesting paper on the application of phylogenetic analysis to the identification of novel psychoactive plants in use as folk remedies by ethnic communities in New York City, treated as a microcosm of global cultural diversity. I presented a synopsis of my work in the Amazon from 2004-2008, in which utilized receptor binding assays as a means of identifying novel psychoactive species, and in the process developed a partial map of the distribution of CNS-active plants in the Amazonian biome.

Further, ethnobotanist Dale Millard reported on recent fieldwork in Northern Mozambique, which resulted in the documentation of a new visionary plant used by medicine men of the Lomwe people. Though known widely as a medicinal plant, the use of Aeschynomene cristata as a visionary medicine (Fabaceae) has not been previously reported. Dr. Kenneth Alper of the Department of Pharmacology and Neurology at the New York University School of Medicine spoke on the current state of research with Iboga (Tabernanthe iboga) and its major alkaloid, Ibogaine, in the treatment of opiate dependence in urban populations. Jean Francios Sobiecki spoke on the parallels and differences between the utilization of initiatory plants in South American and South African shamanic traditions. The final Keynote by Dr. Michael Heinrich, Director of the Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy Research Group of the School of Pharmacy, University College, London, surveyed the emergence of ethnopharmacology as a trans-discipline over the last 50 years, focusing, as an example, on the interdisciplinary research on the psychoactive Mexican mint, Salvia divinorum that led from initial ethnobotanical reports in the mid-1960s, to the isolation of its primary constituent, the diterpene Salvinorin A, in 1982, to subsequent pharmacological investigations in 2002 by Brian Roth and colleagues that characterized it as the most selective and potent Kappa opiate agonist yet identified in or out of nature.

Even a symposium such as ESPD50 can never hope to comprehensively review all the developments in psycho-ethnopharmacology in the last 50 years, and that was never its intent. Rather, it was meant to review some of the highlights in this field over the last five decades, to point the direction of future investigations, and to demonstrate that more psycho-ethnopharmacological discoveries remain to be made. It is hoped that it will serve as an inspiration to a younger generation, and that their work may be presented in future symposia of this sort. We may hope that it will take much less than 50 years for their research to be made known to science and the general public.